For 50 years, the government of South Africa used legislation to enforce racial segregation called apartheid. The idea of segregation in South Africa had its origins before apartheid however. In 1913, the three year old nation passed the Land Act, which required the Black population live on reserves and made it illegal for them to work as sharecroppers. Opponents of this act would forge together to form the South African National Native Congress, which would later become the African National Congress (ANC).

The negative repercussions from the Great Depression and World War II on South Africa’s economy convinced the government to make their racial segregation practices stronger. In 1948, the Afrikaner National Party took control of the government with their slogan as “apartheid”, or separateness; they not only strived to separate the White minority of the country from the non-White majority, but to also separate the non-White majority from each other to decrease their power in the government. This included dividing the Black population of South Africa via tribal lines.

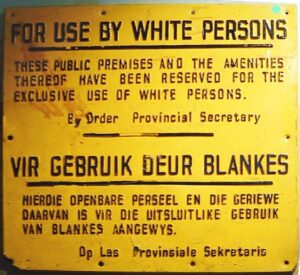

South Africa started passing apartheid laws in 1950. Marriages and sexual relations between Whites and other races were banned. The Population Registration Act of 1950 introduced the government’s classifications of race: Bantu (Black Africans), Colored (mixed), White, and Asian (Indian and Pakistani). This legislation had the ability to split families, as parents and children could be potentially registered as different races. A series of Land Acts also set aside over 80 percent of the country’s land to its White citizens. The government required non-White citizens to carry around passes authorizing their presence in restricted areas; created separated facilities for Whites and non-Whites to limit their communication; limited the action of non-White labor unions and refused non-White participation in the national government.

Upon becoming prime minister in 1958, Dr. Hendrik Verwoerd would further refine apartheid into a system of “separate development”. Ten Bantu homelands, known as Bantustans, were created by the Promotion of Bantu Self-Government Act of 1959. The separation of the Black South Africans from one another allowed the government to claim there was no “real” majority as well as to reduce the possibility that the seperate groups would unite in a nationalist organization. Black South African citizens were forced out of rural areas designated for Whites to these homelands so that the government could sell their land to Whites very cheaply. From 1961 to 1994, more than 3.5 million people were forcibly removed from their homes and deposited in the Bantustans, which were usually ridden with poverty and a despairing lifestyle.

Opposition to this system steadily built over the years. Originating with peaceful protests and strikes, the ANC held a mass meeting in 1952 that was broken up by the government. 150 people were arrested and charged with high treason. In 1960, in a Black township called Sharpesville, police fired on an unarmed group of Blacks who belonged to the Pan-African Congress, a group that worked with the ANC. 67 Blacks were killed and over 180 were wounded. This incident made many anti-apartheid leaders realize that peaceful protest was not effective, so military wings of the protest groups developed. Although none of the groups posed that much of a military threat, almost all of the resistance leaders were in prison or executed by 1961. Founder of the ANC’s branch, Umkhonto we Sizwe (“Spear of the Nation”), Nelson Mandela was incarcerated from 1963 to 1990; his imprisonment gave international recognition to the apartheid cause.

When a 1976 protest, one of children demonstrating against language requirements in school, was broken up by tear gas and bullets, the government increasingly cut down on those opposed to apartheid. Combined with an economic recession, this brought South Africa attention on the world stage. The United Nations General Assembly denounced apartheid in 1973 and three years later voted to put a mandatory embargo of arms to the nation. In 1985, the United Kingdom and United States imposed economic sanctions on South Africa. The national party under Pieter Botha tried to make legislative changes due to this pressure, but they were seen as not substantive enough and F.W. de Klerk took control of the government in 1989. De Klerk’s government repealed the majority of the legislation that apartheid was built upon and a new constitution took effect in 1994. Elections that following year led to a coalition government with a non-White majority, marking the official end of the apartheid system.

Back to Crime Library

|

|

|